3 Storing data in spreadsheets and understanding tabular data

We have previously mentioned spreadsheets like those created in Excel. These are great but not great for reproducible science or data analysis. This drawback is because they are not easily documented and scripted. The data is part of the analysis! Another danger with spreadsheets (like MS Excel) is that it re-formats your data. Re-formatting is such a big problem for scientists that they have started renaming genes to avoid confusion1

1 See this.

Errors are frequent in spreadsheets, not only because of renaming (Ziemann, Eren, and El-Osta 2016), but also because of wrong formatting of formulas (Stephen, Kenneth, and Barry 2009). These are both reasons for using spreadsheets only for what they do best: data input and storage (Broman and Woo 2018). Before going in to details about how to use your spreadsheet software and to avoid catastrophe, it’s good to know a little about the capabilities of your spreadsheet software.

3.1 Cells and simple functions

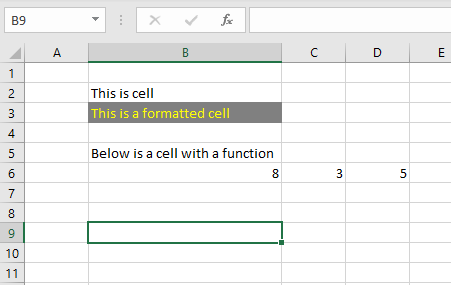

A spreadsheet consists of cells, these can contain values, such as text, numbers, formulas and functions. Cells may also be formatted with attributes such as color or text styles. Below is an example of some data entered in a spreadsheet (Figure 3.1).

Cell B6 contains a simple formula: = C6 + D6. This formula adds cells C6 and D6 resulting in the sum, 8. In formulas, mathematical operators can be used (\(+, -, \times , \div\) ). Formulas can be also extended with inbuilt function such as showed in Table 3.1.

| Function | English | Norwegian |

|---|---|---|

| Sum | SUM() |

SUMMER() |

| Average | AVERAGE() |

GJENNOMSNITT() |

| Standard deviation | STDEV.S() |

STDEV.S() |

| Count | COUNT() |

ANTALL() |

| Intercept | INTERCEPT() |

SKJÆRINGSPUNKT() |

| Slope | SLOPE() |

STIGNINGSTALL() |

| If | IF() |

HVIS() |

The sum, average, standard deviation, and count are simple functions for summarizing data. Intercept and slope are functions used to get simple associations from two sets of numbers (based on a regression model). The IF function is an example of a function that can be used to enter data in a cell conditionally. For example, IF cell A1 contains a certain number, then cell B1 should display another specified text.

When looking for tips and tricks online, you may come across functions for excel in other languages than what is installed on your computer. To translate functions and for a complete overview of functions included in Microsoft Excel, see this website en.excel-translator.de/.

3.2 Tidy data and data storage

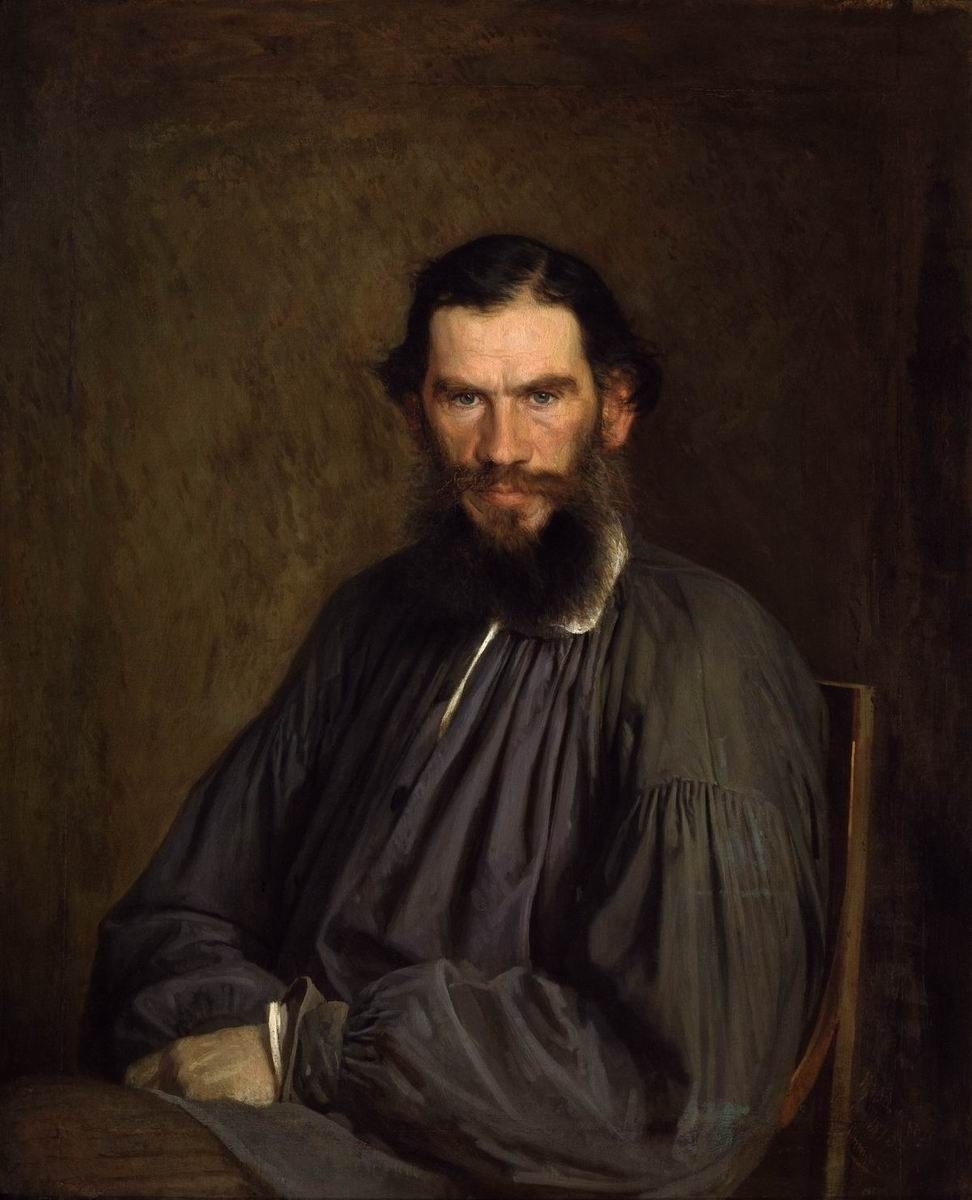

Hadley Wickham (the author of many commonly used R packages) quotes Tolstoy when describing the principle of tidy data (Wickham 2014). This Tolstoy quote is so famous that it has given name to a principle. The principle in turn comes in many variants but basically states that there are endless possibilities for something to break but only a limited number of ways that same thing can work2. This principle can be applied to data sets. There are endless ways that formatting of data sets can be problematic, but a limited set of ways that formatting will allow for analysis.

2 See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anna_Karenina_principle

A tidy data set consists of values originating from observations and belonging to variables. A variable is a definition of the values based on attributes. An observation may consist of several variables (Wickham 2014). A tidy data set typically has one observation per row and one variable per column.

Let’s say that we want to collect data from a strength test. A participant (participant identification is a variable) in our study conducts tests before and after the intervention (time is a variable) in two exercises (exercise is a variable), and we record the maximal strength in kg (load is a variable). The data set will look like the table below (Table 3.2).

| Participant | Time | Exercise | Load |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bruce Wayne | pre | Bench press | 95 |

| Bruce Wayne | post | Bench press | 128 |

| Bruce Wayne | pre | Leg press | 180 |

| Bruce Wayne | post | Leg press | 280 |

Another example contains variables that actually carries two pieces of information in one variable. We again did a strength test, this time as maximal isometric contractions and in each test consisted of two attempts. We record this in two different variables, attempt 1 and 2. The resulting data set could look something like in Table Table 3.3.

| Participant | Time | Exercise | Attempt1 | Attempt2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selina Kyle | pre | Isometric | 81.3 | 92.5 |

| Selina Kyle | post | Isometric | 97.1 | 114.1 |

To make this data set tidy we need to extract the attempt information and record it in another variable as seen in Table 3.4.

| Participant | Time | Exercise | Attempt | load |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selina Kyle | pre | Isometric | 1 | 81.3 |

| Selina Kyle | pre | Isometric | 2 | 92.5 |

| Selina Kyle | post | Isometric | 1 | 97.1 |

| Selina Kyle | post | Isometric | 2 | 114.1 |

This transformation naturally gives additional rows to the data set. It is sometimes referred to as “long format” data instead of the structure where each attempt is given separate variables, called “wide format.” You will notice during the course that the long format is convenient for most purposes. This is true when we create graphs and do statistical modelling. But sometimes, a variable must be structured in a wide format to allow certain operations.

If we follow what is recommended by Broman and Woo (Broman and Woo 2018), it is clear that each cell in a spreadsheet should only contain one value. If we, for example, decide to format a cell to a certain colour, we add data to that cell on top of the actual data. You might add colour to a cell to remember to add or change data. However, this information is lost when you use the data set in other software. Instead, you should add another variable to allow such data to be properly recorded. Using a variable called comments, you can add text describing information about that particular observation, information that is not lost when you use the data set in another software.

3.3 Recording data

A trade secret3 from people who work all day with data and programming is that they are lazy. Lazy in the sense that you want to type as little as possible and avoid moving your arm to the computer mouse whenever possible. When recording data, we can be lazy too. We can do this by shortening variable names and not using CAPITAL letters when entering text in data storage. After a hard day at the keyboard, you will be happy to write strtest instead of Strength Test. The extra effort of using two capital letters might be the thing to tip you over the edge. However, we should not be too lazy either; variable names and values should be “short but meaningful” (Broman and Woo 2018).

3 A trade secret as in “not generally known to the public”. See en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trade_secret.

Data and variables should also be consistent. Do not mix data type; use a consistent way of entering e.g., dates and time, and do not use spaces or special characters. To enforce this, you might want to start your data collection by writing up a data dictionary describing all variables you collect. The dictionary can set the rules for your variables. This dictionary can also guide your data validation.

In Excel, you can use data validation to set rules for data entry. For example, if you have a numeric variable, you can set Excel only to accept numbers in a specified set of cells. Such rules make it harder to enter erroneous data.

3.4 Saving data

Data from spreadsheets can be saved as special spreadsheet files, such as .xlsx. This format allows for functions, multiple spreadsheets in the same file (tabs), and cell formatting. You do not need this fancy format if you follow the tips described above and in (Broman and Woo 2018). Instead, you can store your data as a .csv file. This format may be read and edited with Excel (or another spreadsheet software) and in plain text. Data entered in this format (comma-separated values; csv) can look like this in a text editor:

Participant;Time;Exercise;Attempt;load

Selina Kyle;pre;Isometric;1;81.3

Selina Kyle;pre;Isometric;2;92.5

Selina Kyle;post;Isometric;1;97.1

Selina Kyle;post;Isometric;2;114.1This format is quite lovely. The data takes little space; the simple format requires that data is well documented using e.g., a data dictionary; and it is available for many other software as the format is simple. You can document the data using a README file that could describe the purpose and methods of data collection, how the data is structured, and what kind of data the variables contains. A simple README file can be written in a text editor such as Notepad and saved as a .txt file. Later in this course, we will introduce a “markup” language often used to create README files containing a syntax that formats the text to a more pleasant style when converted to other formats.