Code

library(tidyverse)

ggplot(data = data.frame(x = c(-4, 4)), aes(x)) +

stat_function(fun = dt, n = 1000, args = list(df = 9)) + ylab("") +

scale_y_continuous(breaks = NULL) +

labs(x = "") +

theme_classic()

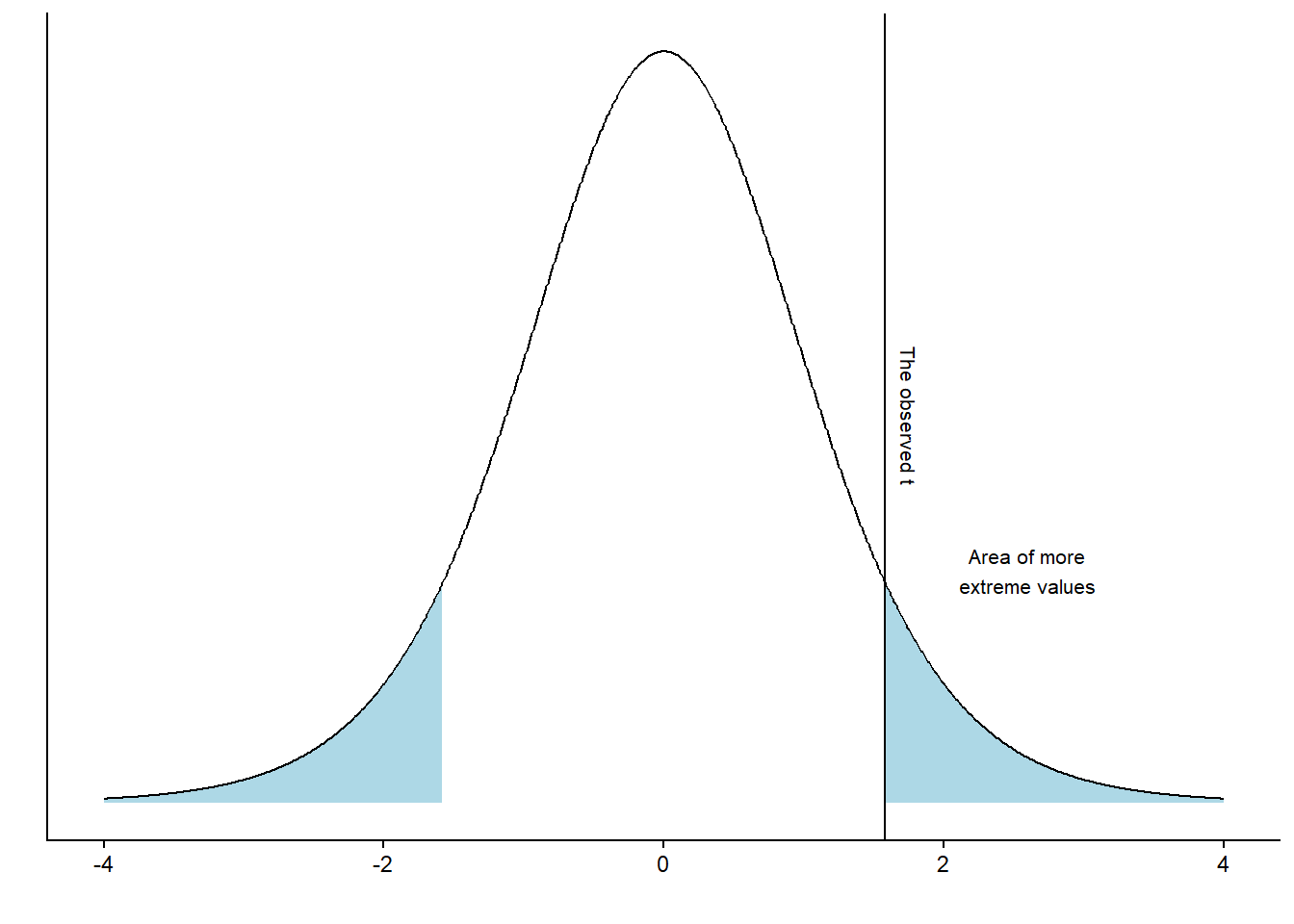

Consider the sampling distribution. This is an imaginary distribution of, e.g., sample means gathered from repeated sampling from a population of numbers. Let’s say we have a null hypothesis, H0. This hypothesis states that the population mean is zero. We draw a sample of $ n=10 $, and our sample indicates that it is not zero, it is about 1. We calculate the standard deviation of our sample, which is 2.

Based on these numbers, we can calculate a sample statistic, a t-value

\[t = \frac{m - \mu}{s/\sqrt{n}}\]

where \(m\) is our sample mean, \(\mu\) is the hypothesized mean, \(s\) is our sample standard deviation and \(n\) is the sample size. As we have covered in the previous chapter, we do not know the true variation in the imaginary distribution of samples, but \(s\) is our best guess of the population standard deviation. Using \(s\), we can model the imaginary sampling distribution by calculating the standard error. This is our best guess of the standard deviation of the sampling distribution.

It would look something like this (Figure 14.1).

library(tidyverse)

ggplot(data = data.frame(x = c(-4, 4)), aes(x)) +

stat_function(fun = dt, n = 1000, args = list(df = 9)) + ylab("") +

scale_y_continuous(breaks = NULL) +

labs(x = "") +

theme_classic()

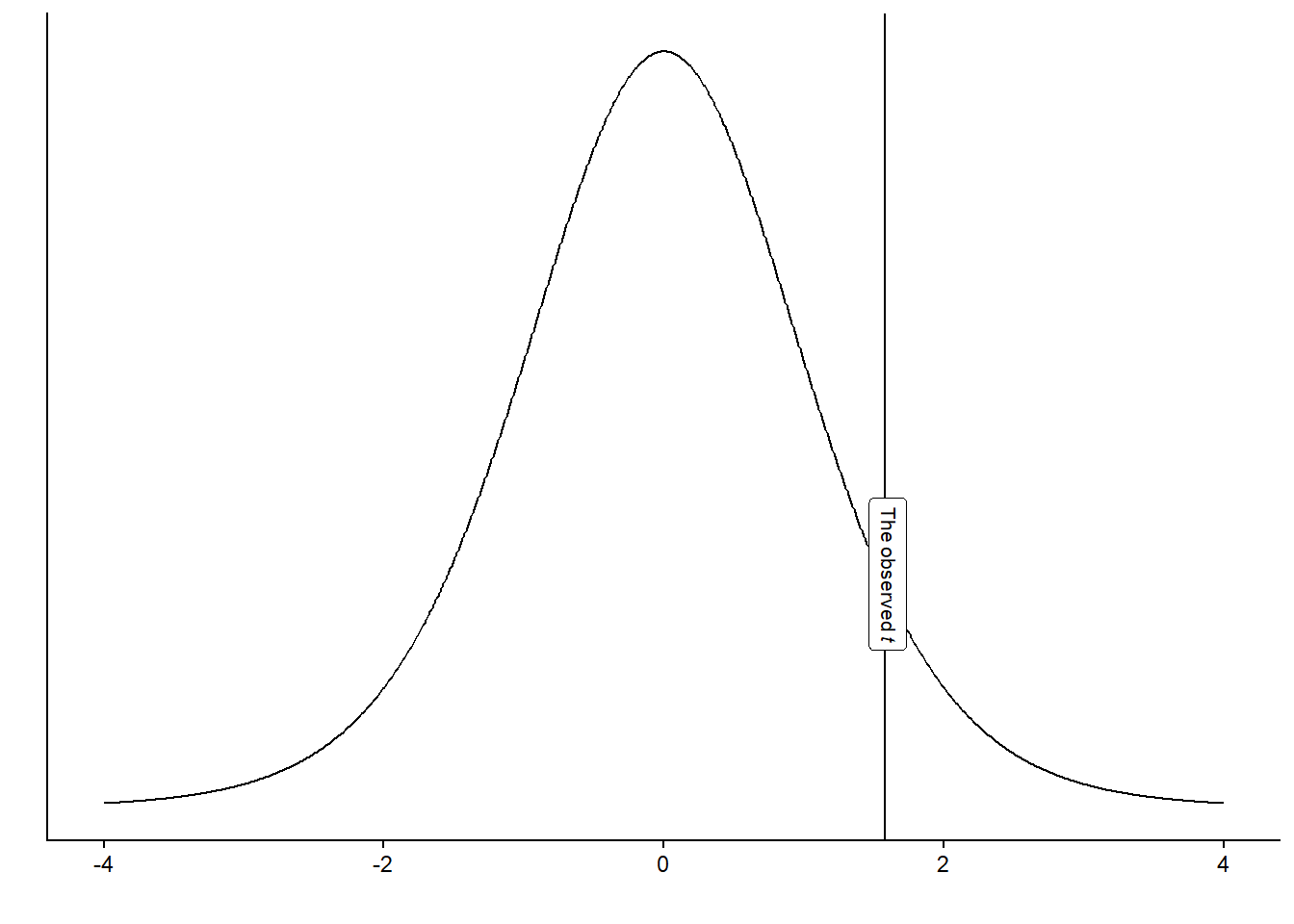

The distribution above is the t-distribution with 10-1 degrees of freedom. Our calculated sample statistic can be inserted into the figure to illustrate how far our observed value is from the null hypothesis.

library(ggtext)

ggplot(data = data.frame(x = c(-4, 4)), aes(x)) +

stat_function(fun = dt, n = 1000, args = list(df = 9)) + ylab("") +

scale_y_continuous(breaks = NULL) +

geom_vline(xintercept = (1-0) / (2/sqrt(10))) +

annotate("richtext",

x = 1.6,

size = 2.8,

y = 0.12,

label = "The observed *t*",

angle = -90) +

labs(x = "") +

theme_classic()

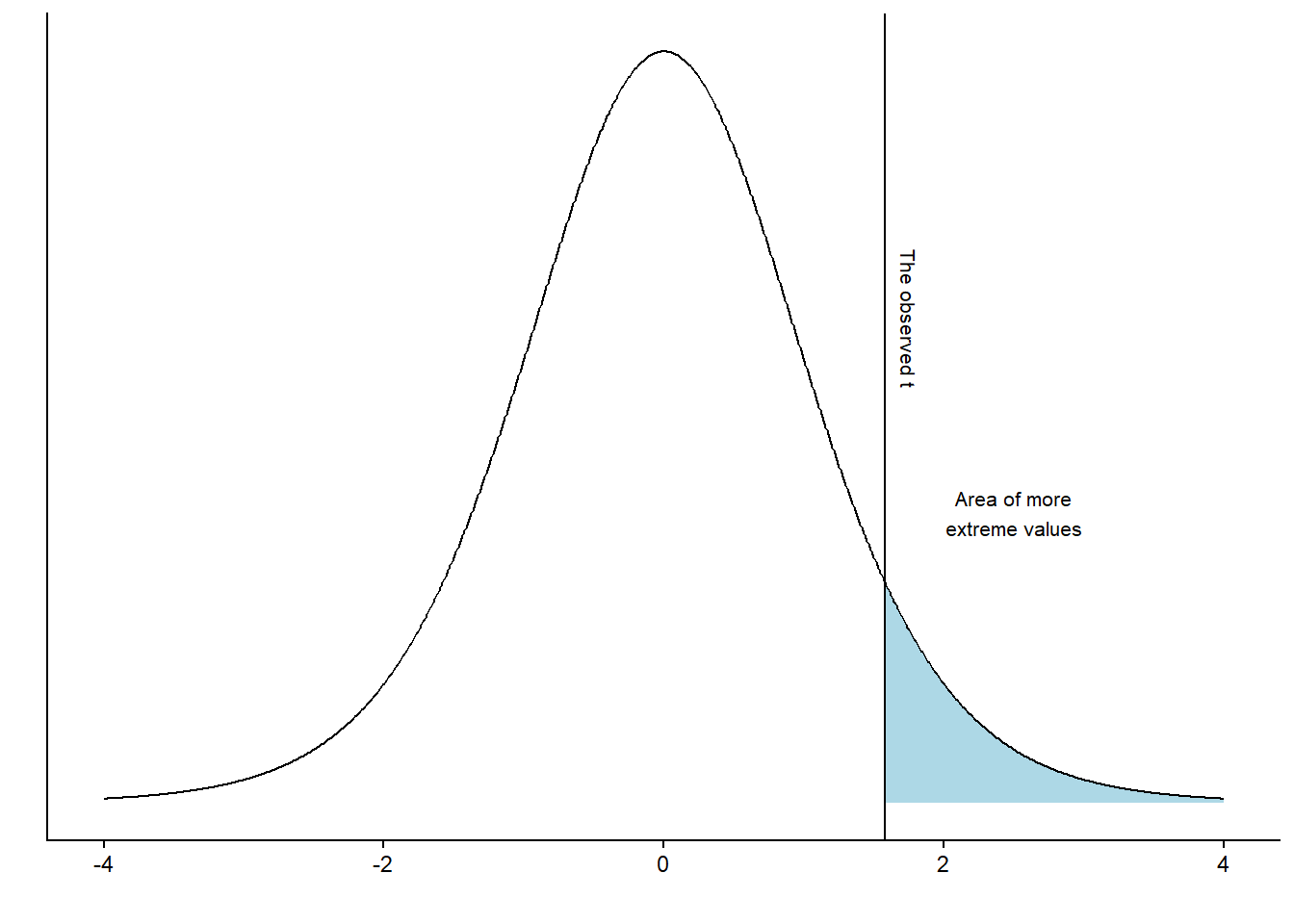

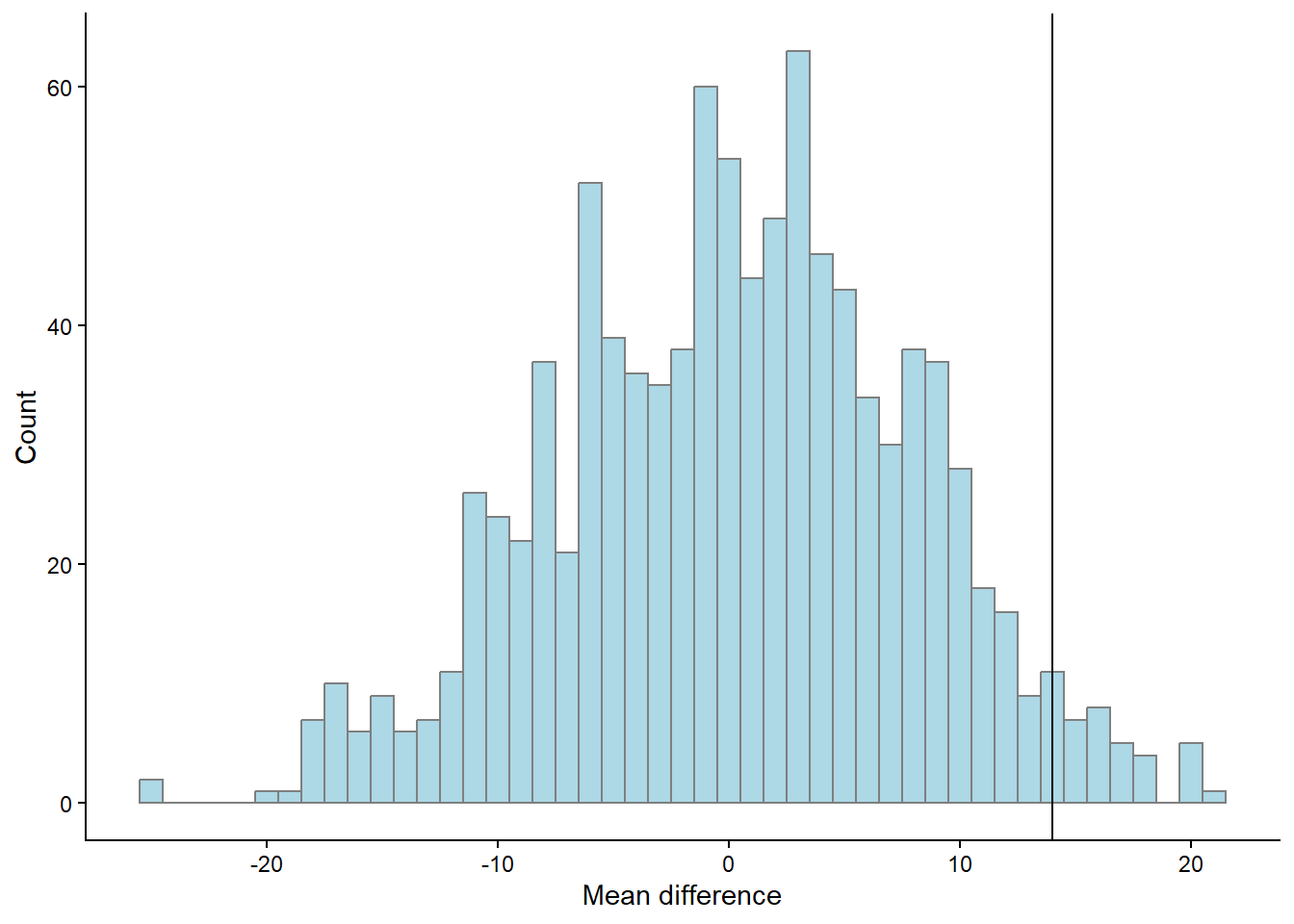

Using the calculated t-value, we may answer questions like: “If the null-hypothesis is true, how often would we observe our t-value, or an even more extreme value, if we repeated our study ?” We can calculate this from the imaginary distribution as the area under the curve above our value.

library(tidyverse)

ggplot(data = data.frame(x = c(-4, 4)), aes(x)) +

stat_function(fun = dt,

args = list(df = 9),

xlim = c(4, (1-0) / (2/sqrt(10))),

geom = "area", fill = "lightblue") +

stat_function(fun = dt, n = 1000, args = list(df = 9)) + ylab("") +

scale_y_continuous(breaks = NULL) +

geom_vline(xintercept = (1-0) / (2/sqrt(10))) +

annotate("text", x = 1.75, y = 0.25, label = "The observed t",

size = 2.8, angle = -90) +

annotate("text", x = 2.5, y = 0.15,

size = 2.8, label = "Area of more\nextreme values") +

labs(x = "") +

theme_classic()

t <- (1-0) / (2 / sqrt(10))

p <- pt(t, df = 10-1, lower.tail = FALSE)

In R, this area can be calculated using the pt() function:

t <- (1-0) / (2 / sqrt(10))

pt(t, df = 10-1, lower.tail = FALSE)

It turns out that 7% of the distribution can be found in the blue shaded area. Using the procedure above, we have completed a one-sample t-test. However, we have to reexamine our null hypothesis, which states \(H_0 = 0\). There are two ways to disprove this hypothesis. We may find out that the value is lower or higher than 0. To account for both possibilities, we calculate a two-sided p-value. In practice, we calculate the area under the curve above and below values corresponding to our observed distance from 0 (Figure 14.4).

2 * pt(t, df = 10-1, lower.tail = FALSE)

library(tidyverse)

ggplot(data = data.frame(x = c(-4, 4)), aes(x)) +

stat_function(fun = dt,

args = list(df = 9),

xlim = c(4, (1-0) / (2/sqrt(10))),

geom = "area", fill = "lightblue") +

stat_function(fun = dt,

args = list(df = 9),

xlim = c(-4, -(1-0) / (2/sqrt(10))),

geom = "area", fill = "lightblue") +

stat_function(fun = dt, n = 1000, args = list(df = 9)) + ylab("") +

scale_y_continuous(breaks = NULL) +

geom_vline(xintercept = (1-0) / (2/sqrt(10))) +

annotate("text", x = 1.75, y = 0.2, label = "The observed t", angle = -90,

size = 2.8) +

annotate("text", x = 2.6, y = 0.12, label = "Area of more\nextreme values",

size = 2.8) +

labs(x = "") +

theme_classic()

p <- 2 * pt(t, df = 10-1, lower.tail = FALSE)

As the area under the curve in the blue area is 14.8% of the distribution we may make a statement such as: “If the null-hypothesis is true, our observed value, or a value even more distant from 0 would appear 14.8% of the times upon repeated sampling”.

We cannot really reject the null hypothesis, as the result of our test (our t-value, or a more extreme value) is so commonly observed if the \(H_0\) distribution is true.

You sample a new mean from \(n=10\) of 1.45, the standard deviation is 2.1. What is the t-statistic and the corresponding p-value with the \(H_0 = 0\). Is the evidence strong enough for you to decide in favor of the alternative hypothesis?

t <- (1.45 - 0) / (2.1/sqrt(10))

p <- 2 * pt(t, df = 10-1, lower.tail = FALSE)Given the test statistics, we get a p-value of 0.057, which corresponds to flipping a coin and getting heads 4 times in a row. The recalculation of the p-value into, e.g., a value corresponding to the number heads in a row when flipping a fair coin, is called the surprisal value, or S-value (Rafi and Greenland 2020). This technique has been suggested to aid in interpreting the p-value. Critically, the S-value provides the surprise factor against the test hypothesis (Rafi and Greenland 2020).

Side note: Printing numbers in R: Sometimes, a ridiculous number appears in your console, such as \(4.450332e-05\). This is actually \(0.00004450332\) written in scientific notation.

e-05can be read as \(10^{-5}\). Rounding numbers in R is straightforward. Just useround(4.450332e-05, digits = 5)to round the number to 5 decimal points. However, you will still see the number in scientific notation. If you want to print the number with all trailing zeros, you can instead usesprintf("%.5f", 4.450332e-05). This function converts the number into text and prints what you want. The “%.5f” sets the number of decimal points to 5. This isn’t very intuitive, I know!

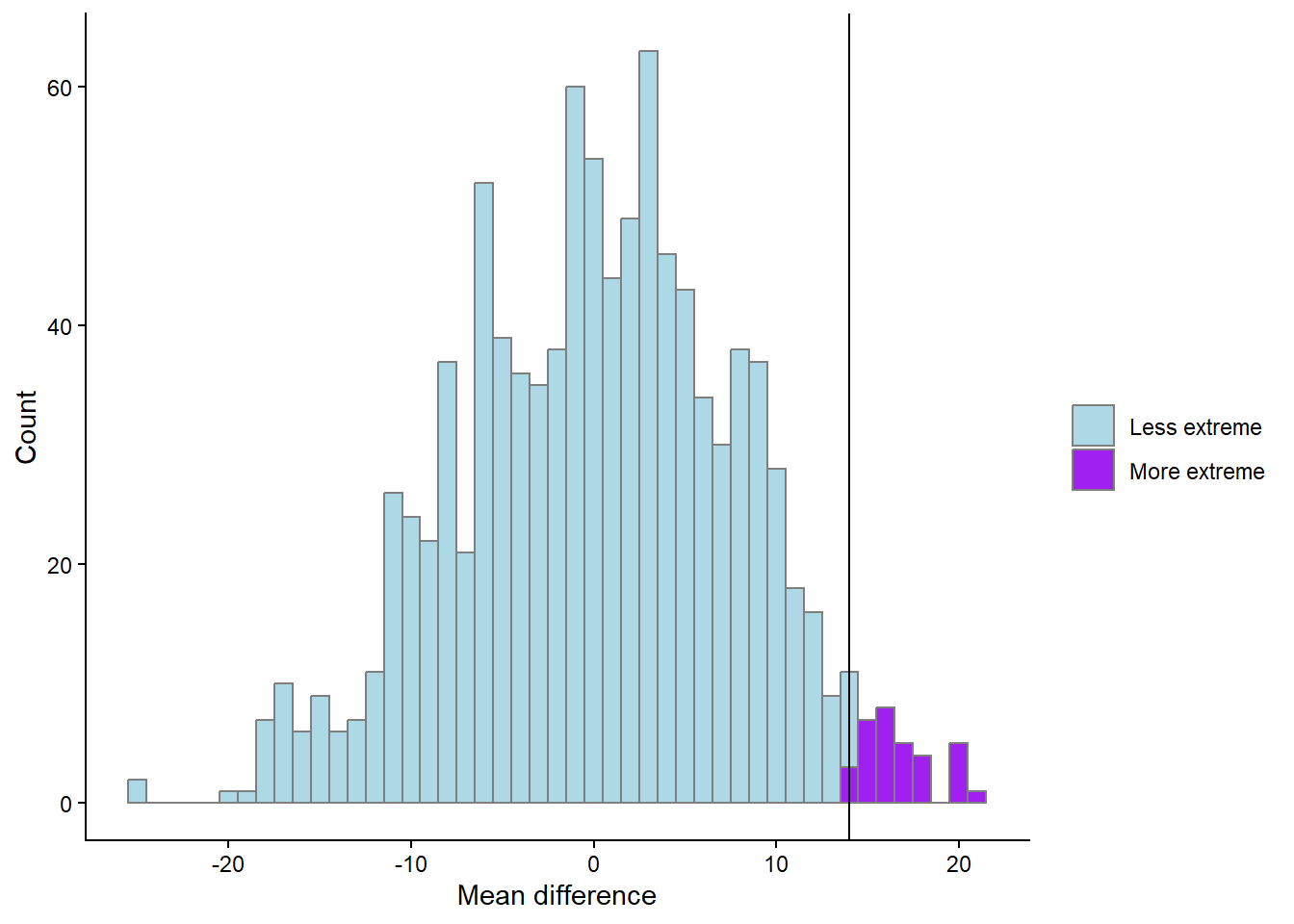

In a two-sample scenario, we can model the null hypothesis using data reshuffling. We sample two groups: one group has done resistance training, and the other has done endurance training. We want to know whether you get stronger from strength training compared to endurance training. We measure the groups after an intervention. They were similar before training, so we think it is OK to measure post-training 1RM bench press values.

These are:

strength.group <- c(75, 82.5, 87.5, 90, 67.5, 55, 87.5, 67.5, 72.5, 95)

endurance.group <- c(67.5, 75, 52.5, 85, 55, 45, 47.5, 85, 90, 37.5)We can calculate the difference between the groups as:

mean.difference <- mean(strength.group) - mean(endurance.group)We can simulate the null-hypothesis (\(H_0\)) by removing the grouping and sample at random into two groups. Read the code below and try to figure out what it does.

set.seed(123)

results <- data.frame(m = rep(NA, 1000))

for(i in 1:1000){

# Here we combine all observations

all.observations <- data.frame(obs = c(strength.group, endurance.group)) %>%

# based on a random process each iteration of the for-loop assign either endurance or strength to each individual

mutate(group = sample(c(rep("strength", 10),

rep("endurance", 10)),

size = 20,

replace = FALSE)) %>%

group_by(group) %>%

summarise(m = mean(obs))

# calculate the difference in means and store in the results data frame

results[i, 1] <- all.observations[all.observations$group == "strength", 2] - all.observations[all.observations$group == "endurance", 2]

}

results %>%

ggplot(aes(m)) + geom_histogram(fill = "lightblue", color = "gray50", binwidth = 1) +

geom_vline(xintercept = mean.difference) +

labs(x = "Mean difference",

y = "Count") +

theme_classic()

The graph above (Figure 14.5) show the distribution of reshuffled mean differences. As the reshuffle process was done 1000 times we can count the number of means more extreme than the mean that we did observe.

p <- length(results[results$m > mean.difference,]) / 1000The above code calculates the proportion of mean differences greater than the observed difference that occurred when we re-shuffled the groups by chance. The number of total re-shuffles that are greater than our observation corresponds to 3.3%.

# An illustration of the above

results %>%

mutate(extreme = if_else(m > mean.difference, "More extreme", "Less extreme")) %>%

ggplot(aes(m, fill = extreme)) + geom_histogram(color = "gray50", binwidth = 1) +

scale_fill_manual(values = c("lightblue", "purple")) +

geom_vline(xintercept = mean.difference) +

labs(x = "Mean difference",

y = "Count",

fill = "") +

theme_classic()

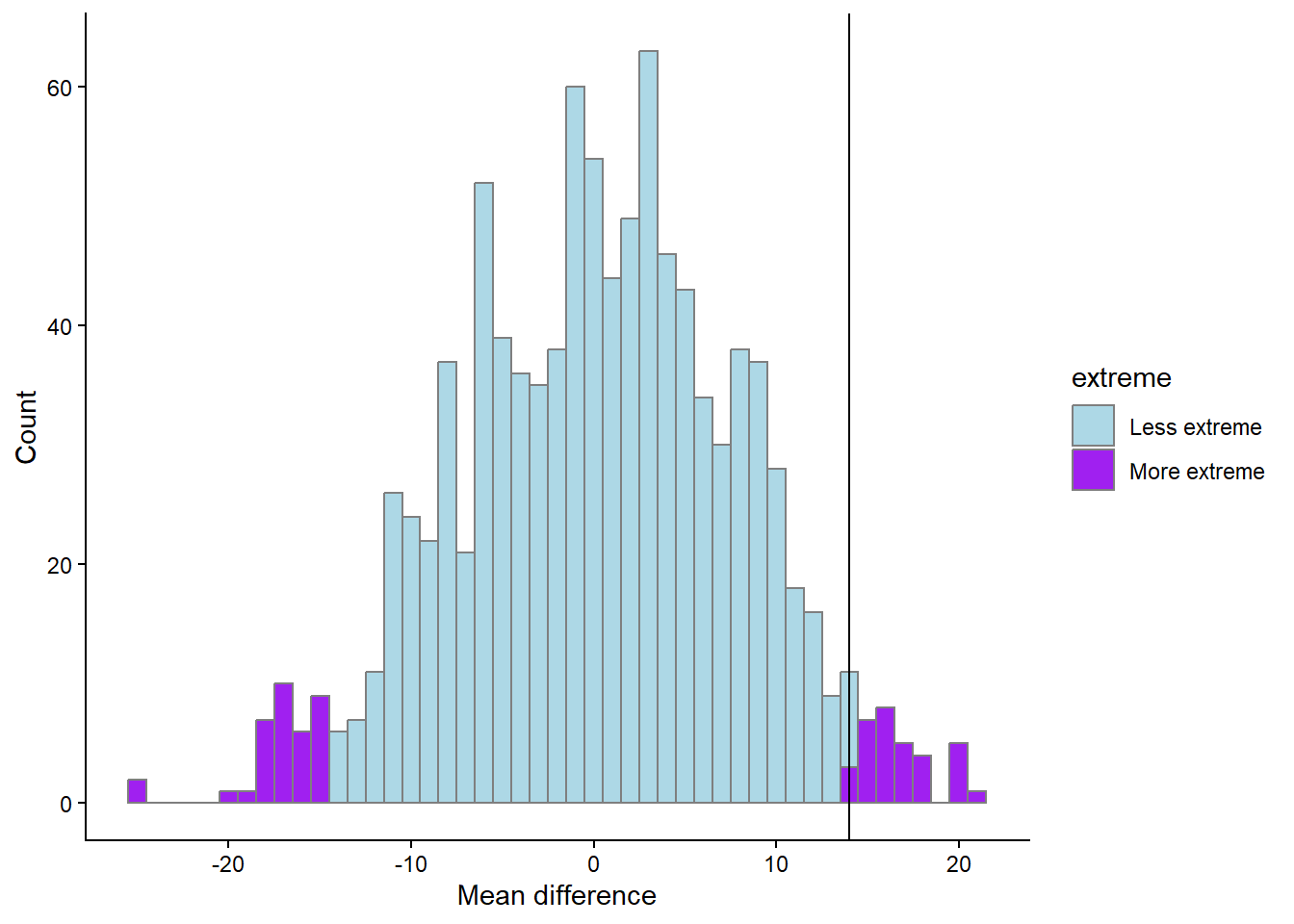

We have now calculated the proportion of values more extreme than the observed. This would represent a directional hypothesis

\[H_A: \text{Strength} > \text{Endurance}\] We can account for the fact that the endurance group could be stronger than the strength group with the figure below (Figure 14.7). Try to figure out what the code does and what has changed from above.

results %>%

mutate(extreme = if_else(abs(m) > mean.difference, "More extreme", "Less extreme")) %>%

ggplot(aes(m, fill = extreme)) + geom_histogram(color = "gray50", binwidth = 1) +

scale_fill_manual(values = c("lightblue", "purple")) +

geom_vline(xintercept = mean.difference) +

labs(x = "Mean difference",

y = "Count") +

theme_classic()

p <- length(results[abs(results$m) > mean.difference,]) / 1000

The proportion of more extreme values, irrespective of direction, compared to our observed value is 6.9%.

Above, we have calculated p-values by comparing our results to a reference distribution of what could be observed if the null hypothesis is true. This is how we should understand p-values.

This is a good place to stop and reflect:

In the example above, where we used the reshuffling technique (also called a permutation test), we are limited by the number of times we can reshuffle our data and by the group sizes to produce a valid p-value. As long as the data are approximately normally distributed, we can use a t-test instead. As outlined above, this test uses an imaginary sampling distribution. It compares our results to a scenario in which the null hypothesis is true.

To test against the null hypothesis that the means of the groups described above are equal, we would use a two-sample t-test. In R, we could perform this test with the following code.

t.test(x = strength.group,

y = endurance.group,

paired = FALSE,

var.equal = TRUE)

Two Sample t-test

data: strength.group and endurance.group

t = 1.9451, df = 18, p-value = 0.06756

alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

-1.121613 29.121613

sample estimates:

mean of x mean of y

78 64 The output of the two-sample t-test contains information on the test statistic t, the degrees of freedom for the test and a p-value. It even has a statement about the alternative hypothesis. We get a confidence interval of the mean difference between groups.

The t-test is quite flexible; we can do one-sample and two-sample t-tests. We can account for paired observation, as when the same participant is measured twice under different conditions. In the one-sample case, we test against the null-hypothesis that a mean is equal to \(\mu\) where we specify the mu in the function. If we have paired observations, we set paired = TRUE. In such a case, each row must correspond to the same individual (or unit).

When we assume that the groups have equal variance (var.equal = TRUE) this corresponds to the classical two-sample case. A more appropriate setting is to assume that the groups do not have equal variance (spread), this is the Welch two-sample t-test (var.equal = FALSE).

In R, by saving a t-test to an object, we can access different results from it. To see which parts we can access, we may use the names function, which returns the names of the various parts of the results.

ttest <- t.test(strength.group, endurance.group, paired = FALSE, var.equal = FALSE)

names(ttest)To access the confidence interval, we would use ttest$conf.int.

Up to now, we have not explicitly talked about the level of evidence needed to reject the null-hypothesis. In classical statistics (frequentist statistics), this level relates to the nature of the scientific question. We can make two types of errors in classical frequentist statistics. A type I error occurs when we reject the null hypothesis when it is actually true. A type II error occurs when we fail to reject the null hypothesis when it is actually false.

Suppose we do not care much about making a Type I error. In that case, a research project might conclude that an intervention is beneficial. If not, there is no harm done, as the side effects are not that serious. Another scenario is when we do not want to make a Type I error. For example, if a treatment is ineffective, the potential side effects are unacceptable. In the first scenario, we might accept higher error rates; in the second example, we are not prepared to tolerate a high false-positive rate, as we do not want to recommend a treatment with side effects that is also ineffective.

A type II error might be serious if an effect is actually beneficial, but we fail to detect it, leading to failure to reject the null hypothesis when it is false. As we will discuss later, error rates are connected with sample sizes. In a study design with a large type II error rate due to a small sample size, we risk declaring an important effect as non-significant.

Type I error is the long-run false-positive rate, this is also called the α-level. If we had drawn samples from a population with a mean of 0 and test against the \(H_0: \mu = 0\). A prespecified error rate of 5% will protect us from drawing the wrong conclusion, but only to the extent that we specify. We can show this in a simulation by running the code below.

set.seed(1)

population <- rnorm(100000, mean = 0, sd = 1)

results <- data.frame(p.values = rep(NA, 10000))

for(i in 1:10000){

results[i, 1] <- t.test(sample(population, 20, replace = FALSE), mu = 0)$p.value

}

# filter the data frame to only select rows with p < 0.05

false.positive <- results |>

filter(p.values < 0.05) |>

nrow()

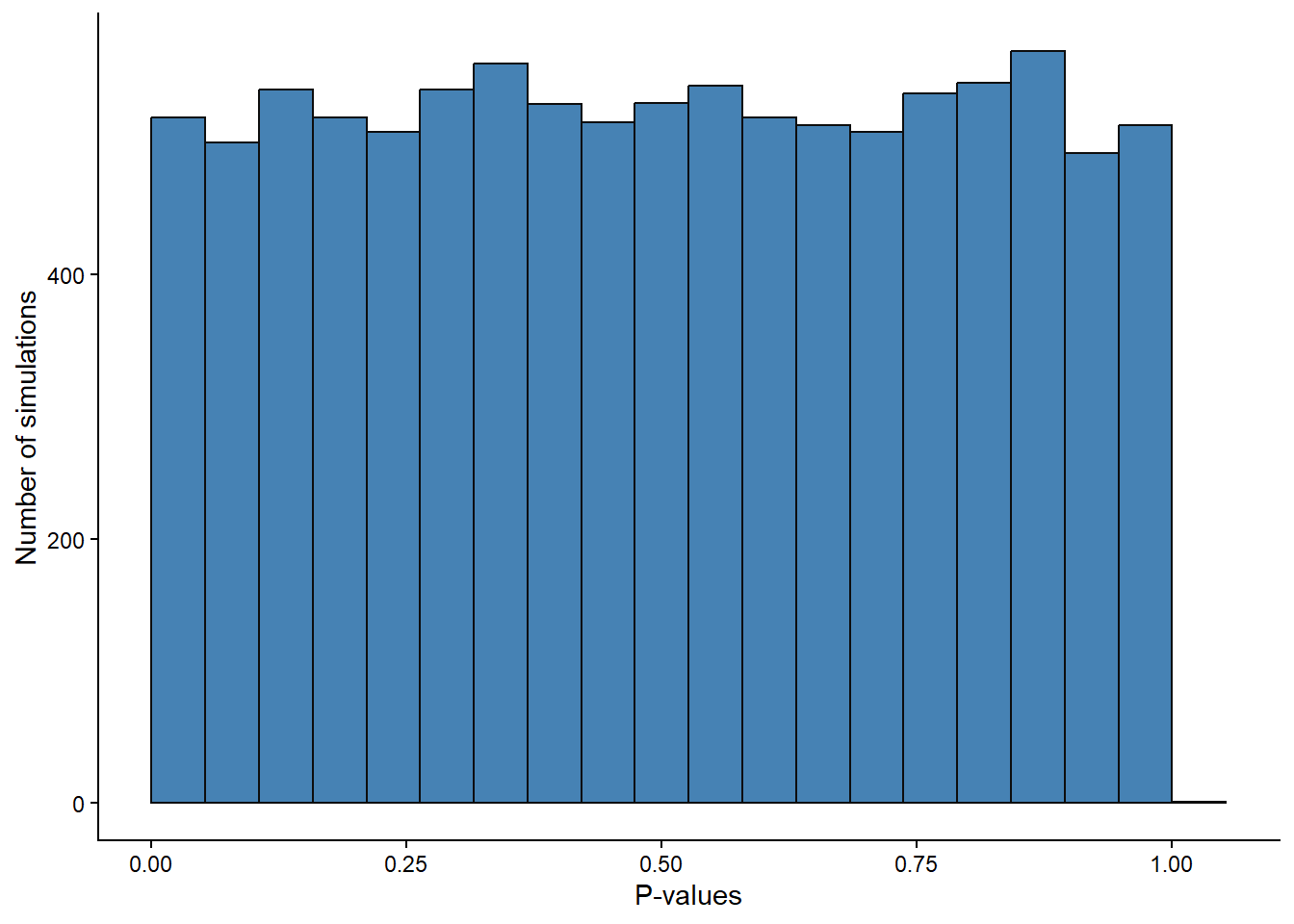

alpha <- false.positive / 10000 # should be ~ 5%When the null-hypothesis is true we will have equally many p-values in the range 0 to 0.05 as between 0.05 and 0.1 and so on. The p-values from 10000 studies have an uniform distribution. We can confirm this by looking at the distribution of p-values in our simulation above (Figure 14.8).

results %>%

ggplot(aes(p.values)) +

geom_histogram(bins = 20,

boundary = 0,

fill = "steelblue",

color = "gray5") +

theme_classic() +

labs(x = "P-values",

y = "Number of simulations")

As the Type II error is defined as the rate at which we accept the null-hypothesis even though it is false, we have to imagine an alternative hypothesis. In the simulation below, we have fixed the true population value to something other than 0. The test is still performed against the null hypothesis, and we declare the observed effect in each simulation iteration as significant when the p-value is below 0.05.

set.seed(1)

population <- rnorm(100000, mean = 0.5, sd = 1)

results <- data.frame(p.values = rep(NA, 10000))

for(i in 1:10000){

results[i, 1] <- t.test(sample(population, 20, replace = FALSE), mu = 0)$p.value

}

# filter the data frame to only select rows with p < 0.05

true.positive <- results %>%

filter(p.values < 0.05) %>%

nrow()

power <- true.positive / 10000 # should be ~ 5%The rate at which a study design successfully declares a true, non-null population effect as significant is called statistical power. It is related to the type II error rate, often denoted β, with 1 - β equal to the power.

In the simulation example above, at a sample size of 20, we use a two-sided one-sample t-test with an α error rate of 5%. This error rate indicates that we will mistakenly declare a population effect corresponding to the null hypothesis as significantly different from 0 in 5% of a series of repeated studies. At the same time, the study design has a 55.8% chance of detecting a true effect of at least 0.5 units away from 0, given a population standard deviation of 1 unit.

Using a specific level of α (the Type I error rate) when analyzing a study affects both the level at which we declare an effect as statistically significant and the width of the confidence interval. This means that a significant effect, identified with p-values, will also produce a confidence interval where the null-hypothesis is not part of the interval.

Transparent reporting of a statistical test include estimates and “the probability of obtaining the result, or a more extreme if the null was true” (the p-value). Estimates may be given together with a confidence interval. The confidence interval gives more information as we can interpret the magnitude of an effect and a range of plausible values of the population effect. Sometimes the confidence interval is large, we may interpret this as having more uncertainty.