# An example function

my_fun <- function(arg1, arg2) { # Name and arguments of the function

# This is the body

sum <- arg1 + arg2

return(sum)

}

my_fun(2, 4)Writing R functions and calculate a lactate threshold

For a comprehensive overview of writing functions in R, Chapter 19 in (Wickham and Grolemund 2017) contains an excellent introduction.

Why write functions

- You should invest in writing functions, if you plan to re-use code by copy paste more than once (Wickham and Grolemund 2017).

- Functions can make your code more readable, reusable and make sure you minimize errors.

- The DRY principle applies → Do not repeat yourself (Wickham and Grolemund 2017).

What is a function?

- R is easily “extended” through the creation of function.

- Functions can live inside package that you or someone else has written.

- Functions can also live in your environment after being defined in your script.

mean(),sd()mutate()andggplot()are examples of functions that comes with the basic installation of R or packages.- For a function to live in your environment, it must have a name

- The function can come with a set of arguments

- The actual mechanics of the function is defined in the body

Naming the function

- The same rules apply to naming functions as other R objects.

- (Wickham and Grolemund 2017) recommend longer and informative/descriptive names written in “snake_case” (as opposed to “camelCase”).

- Be consistent!

- Do not use names of other function!

Arguments

- A function may be defined with named arguments, this is the “input” of the function.

- An argument may be a data frame, a single value or vector that the function will use.

- The function can be used with the arguments used in their place or named out of place.

# An example function

my_fun <- function(value1, value2) { # Name and arguments of the function

# This is the body

diff <- value1 - value2

return(diff)

}

# these are different

my_fun(value2 = 1, value1 = 4)

my_fun(1, 4)Body

- The function body defines the output of the function

- It usually makes use of the data/values/variables defined in the arguments and returns a given output

- Output can be any R object.

- The

return()function is used to explicitly make some part of the body to the output of the function

# An example function

my_fun <- function(value1, value2) { # Name and arguments of the function

# This is the body

diff <- value1 - value2

sum <- value1 + value2

results <- list()

results$diff <- diff

results$sum <- sum

return(results)

}

# these are different

my_fun(value2 = 1, value1 = 4)

my_fun(1, 4)Environment

- If a variable is not defined in the function, R will try to look for it in the environment.

- It is considered good practice to not rely on variables not defined in the function

# An example function

# A variable defined outside the function

value1 <- 3

my_fun <- function(value2) { # Name and arguments of the function

# This is the body

diff <- value1 - value2

sum <- value1 + value2

results <- list()

results$diff <- diff

results$sum <- sum

return(results)

}

my_fun(value2 = 1)

my_fun(5)Conditions, errors and messages

- Functions can include conditional sections, using

ifmakes it possible to make the function flexible depending on input variables

my_fun <- function(value1, value2, calculate.sum = FALSE) {

if (calculate.sum == TRUE) {

sum <- value1 + value2

return(sum)

} else {

print("No sum calculated")

}

}

# Calculates the sum

my_fun(2, 4, TRUE)

# Does not calculate the sum

my_fun(2, 4, FALSE)- A function can stop if the input variable is of the wrong type,

my_fun <- function(value1, value2) {

if (!any(is.numeric(c(value1, value2)))) {

stop("One or more values are not numeric")

} else {

sum <- value1 + value2

return(sum)

}

}

# Calculates the sum

my_fun(value1 = "error?", value2 = 4)

# Does not calculate the sum

my_fun(value1 = 2, value2 = 4)- There are several additional ways to create conditional operations (see (Wickham and Grolemund 2017)).

Group work

- Write a function that is reusable using this code:

z <- df$var1 - mean(df$var1, na.rm = TRUE) / sd(df$var1, na.rm = TRUE)Write a function that stops if the input is not a character vector

Write a function that calculates the standard deviation

\[s=\sqrt{\frac{\sum(x_i-\bar{x})^2}{n-1}}\]

# An example vector

x <- c(2, 5, 7, 8)

# Sum of squares

ss <- sum((x - mean(x))^2)

## Calculates standard deviation

s <- sqrt(ss / (length(x)-1))A function to calculate lactate thresholds

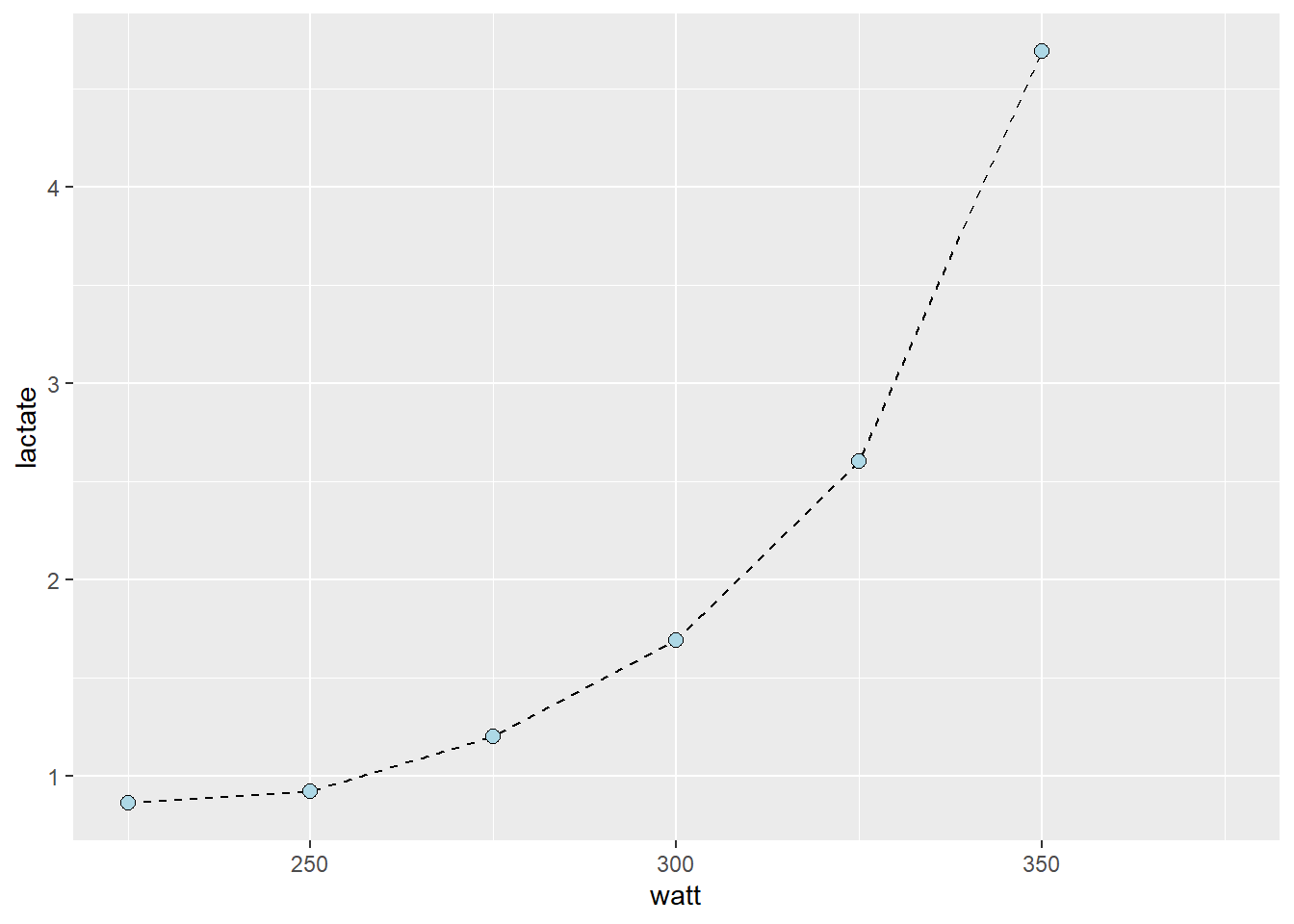

- Lactate threshold (LT) tests are commonly performed in the laboratory

- Calculations of the LT differs between labs and there are many methods

- A possible method is to calculate the power at a fixed lactate value (e.g. 4 mmoL L-1)

library(tidyverse)

library(exscidata)

data("cyclingstudy")

cyclingstudy %>%

# Select columns needed for analysis

select(subject, group, timepoint, lac.225:lac.375) %>%

# Only one participant and time-point

filter(timepoint == "pre", subject == 10) %>%

# Pivot to long format data using the lactate columns

pivot_longer(names_to = "watt",

values_to = "lactate",

names_prefix = "lac.",

names_transform = list(watt = as.numeric),

cols = lac.225:lac.375) %>%

# Plot the data, group = subject needed to connect the points

ggplot(aes(watt, lactate, group = subject)) +

geom_line(lty = 2) +

geom_point(shape = 21, fill = "lightblue", size = 2.5)

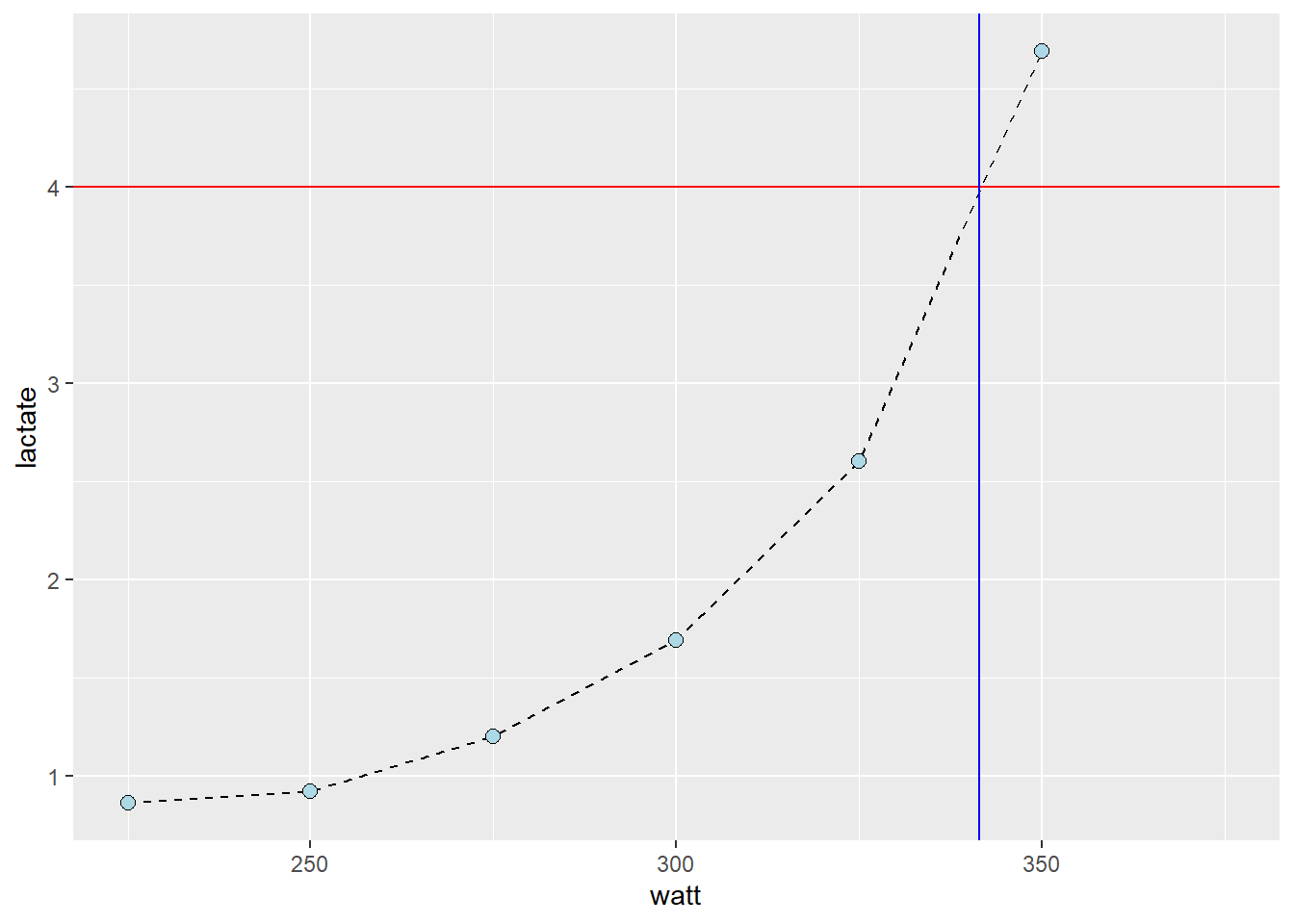

- Manually, we could estimate the watt at a specific lactate using ocular inspection

cyclingstudy %>%

# Select columns needed for analysis

select(subject, group, timepoint, lac.225:lac.375) %>%

# Only one participant and time-point

filter(timepoint == "pre", subject == 10) %>%

# Pivot to long format data using the lactate columns

pivot_longer(names_to = "watt",

values_to = "lactate",

names_prefix = "lac.",

names_transform = list(watt = as.numeric),

cols = lac.225:lac.375) %>%

# Plot the data, group = subject needed to connect the points

ggplot(aes(watt, lactate, group = subject)) +

geom_line(lty = 2) +

geom_point(shape = 21, fill = "lightblue", size = 2.5) +

# Adding straight lines at specific values

geom_hline(yintercept = 4, color = "red") +

geom_vline(xintercept = 341.5, color = "blue")

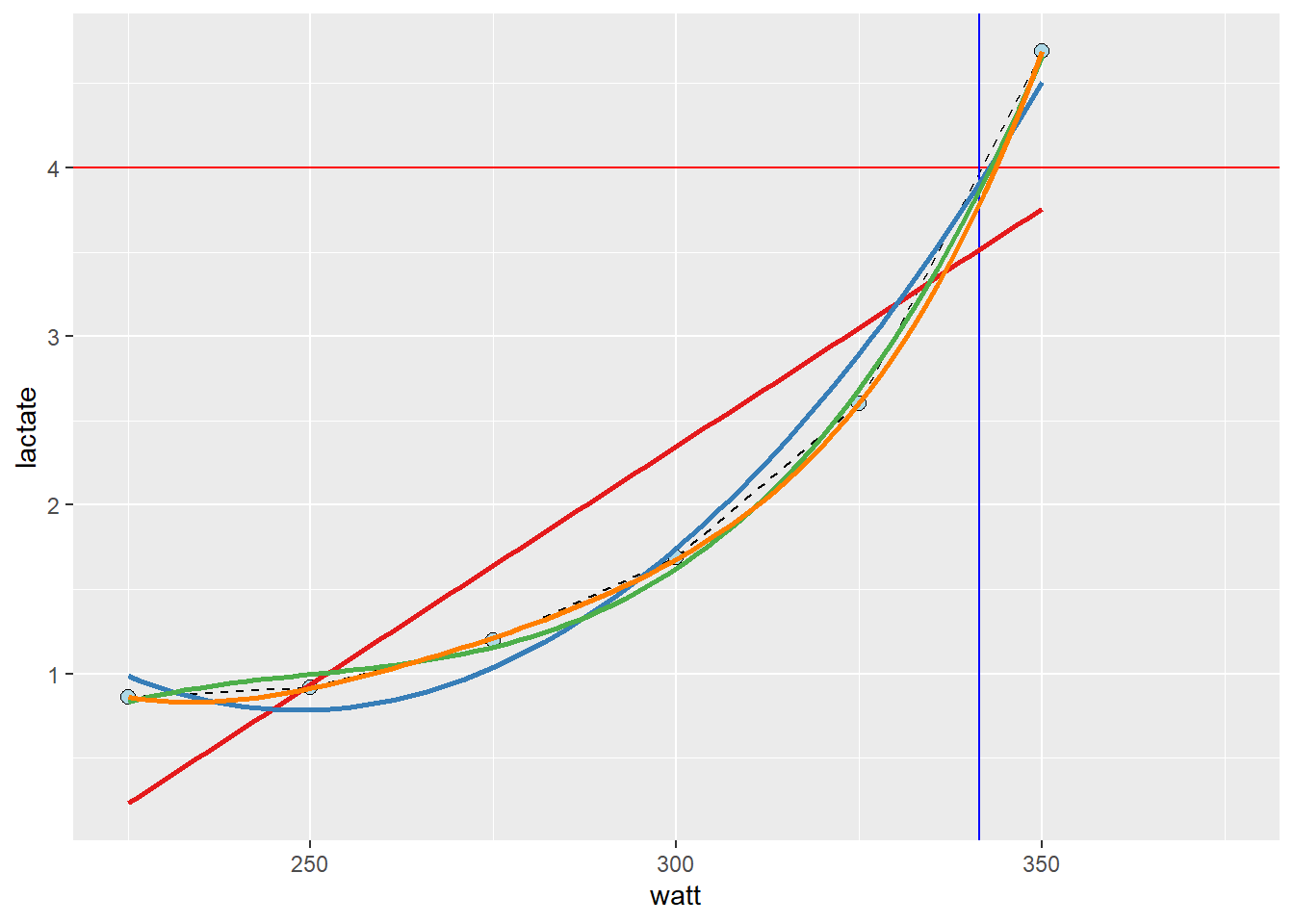

- A better approximation can be derived from the curve linear model

cyclingstudy %>%

# Select columns needed for analysis

select(subject, group, timepoint, lac.225:lac.375) %>%

# Only one participant and time-point

filter(timepoint == "pre", subject == 10) %>%

# Pivot to long format data using the lactate columns

pivot_longer(names_to = "watt",

values_to = "lactate",

names_prefix = "lac.",

names_transform = list(watt = as.numeric),

cols = lac.225:lac.375) %>%

# Plot the data, group = subject needed to connect the points

ggplot(aes(watt, lactate, group = subject)) +

geom_line(lty = 2) +

geom_point(shape = 21, fill = "lightblue", size = 2.5) +

geom_hline(yintercept = 4, color = "red") +

geom_vline(xintercept = 341.5, color = "blue") +

# Adding a straight line from a linear model

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE, formula = y ~ x, color = "#e41a1c") +

# Adding a polynomial linear model to the plot

# poly(x, 2) add a second degree polynomial model.

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE, formula = y ~ poly(x, 2), color = "#377eb8") +

# poly(x, 3) add a third degree polynomial model.

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE, formula = y ~ poly(x, 3), color = "#4daf4a") +

# poly(x, 4) add a forth degree polynomial model.

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE, formula = y ~ poly(x, 4), color = "#ff7f00")

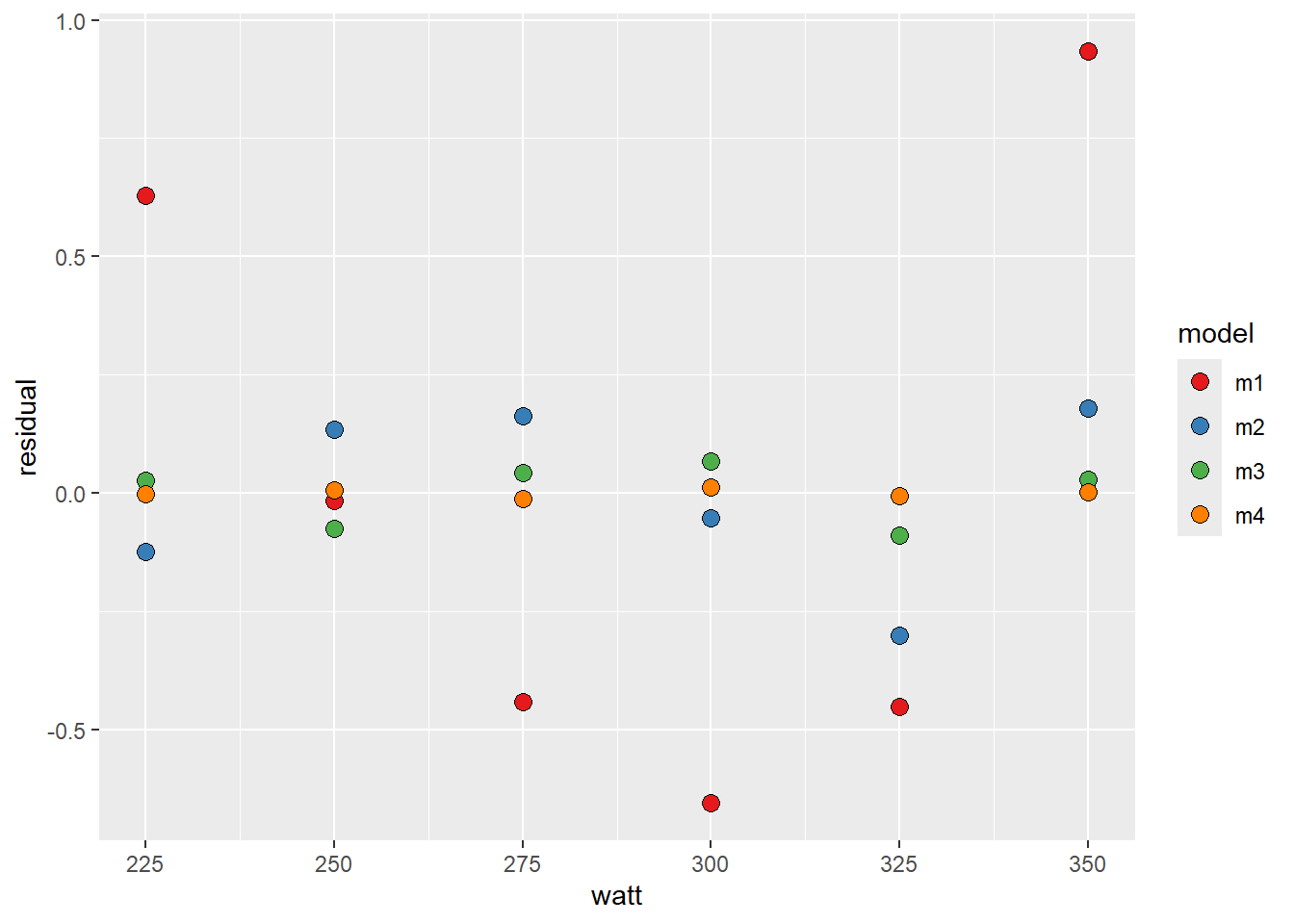

- These models are all “wrong but some are useful”1

lactate <- cyclingstudy %>%

# Select columns needed for analysis

select(subject, group, timepoint, lac.225:lac.375) %>%

# Only one participant and time-point

filter(timepoint == "pre", subject == 10) %>%

# Pivot to long format data using the lactate columns

pivot_longer(names_to = "watt",

values_to = "lactate",

names_prefix = "lac.",

names_transform = list(watt = as.numeric),

cols = lac.225:lac.375) %>%

# Remove NA (missing) values to avoid warning/error messages.

filter(!is.na(lactate))

# fit "straight line" model

m1 <- lm(lactate ~ watt, data = lactate)

# fit second degree polynomial

m2 <- lm(lactate ~ poly(watt, 2, raw = TRUE), data = lactate)

# fit third degree polynomial

m3 <- lm(lactate ~ poly(watt, 3, raw = TRUE), data = lactate)

# fit forth degree polynomial

m4 <- lm(lactate ~ poly(watt, 4, raw = TRUE), data = lactate)

# Store all residuals as new variables

lactate$resid.m1 <- resid(m1)

lactate$resid.m2 <- resid(m2)

lactate$resid.m3 <- resid(m3)

lactate$resid.m4 <- resid(m4)

lactate %>%

# gather all the data from the models

pivot_longer(names_to = "model",

values_to = "residual",

names_prefix = "resid.",

names_transform = list(residual = as.numeric),

cols = resid.m1:resid.m4) %>%

# Plot values with the observed watt on x axis and residual values at the y

ggplot(aes(watt, residual, fill = model)) + geom_point(shape = 21, size = 3) +

# To set the same colors/fills as above we use scale fill manual

scale_fill_manual(values = c("#e41a1c", "#377eb8", "#4daf4a", "#ff7f00"))

- Using the

predict()function we can predict lactate values at a specific power output. - We are modelling the effect of watt on lactate, so we are unable to input a specific lactate value, instead we could approximate with “inverse prediction

ndf <- data.frame(watt = seq(from = 225, to = 350, by = 0.1)) # high resolution, we can find the nearest10:th a watt

ndf$predictions <- predict(m3, newdata = ndf)

# Which value of the predictions comes closest to our value of 4 mmol L-1?

# abs finds the absolute value, makes all values positive,

# predictions - 4 givs an exact prediction of 4 mmol the value zero

# filter the row which has the prediction - 4 equal to the minimal absolut difference between prediction and 4 mmol

lactate_threshold <- ndf %>%

filter(abs(predictions - 4) == min(abs(predictions - 4)))

Group work

- Write a function that calculates the lactate threshold using a fixed lactate value.

- The function should have arguments that defines the data and lactate value

- The output should be a value of the approximate watt at the fixed lactate

References

Wickham, Hadley, and Garrett Grolemund. 2017. R for Data Science: Import, Tidy, Transform, Visualize, and Model Data. 1st ed. Paperback; O’Reilly Media. http://r4ds.had.co.nz/.

Footnotes

See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/All_models_are_wrong↩︎